Your Dog Loses Their Mind Around Other Dogs: Dog-On-Dog Aggression Explained

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn a commission. Here’s how it works.

Walking your dog should not feel like preparing for battle. But if your dog loses their mind the second another dog appears, every walk turns into a high-stress event you dread.

Table of Contents

This does not mean your dog is mean, broken, or dangerous. In many cases, what looks like dog-on-dog aggression is actually fear, frustration, or reactivity, not a desire to hurt another dog.

Start Here: Is This Aggression Or Reactivity?

Many dogs that bark, lunge, or explode on walks are not truly aggressive. They are reactive. That distinction matters because it changes how you respond and what will actually help.

Reactivity is an overreaction to a trigger, often caused by fear, frustration, or excitement. The dog looks intense, but the goal is distance, not damage. True aggression involves intent to harm and continues even when the other dog is no longer a threat.

Most owners are dealing with reactivity, especially on leash. Labeling it as aggression too early often leads to punishment-based fixes that make the problem worse.

Quick Check

- Does your dog calm down once the other dog is gone?

- Is the behavior worse on leash than off?

- Does distance reduce the reaction?

If yes, you are likely dealing with reactivity rather than true dog-on-dog aggression. View our guide covering aggressive dog training tips for help.

Common Signs Of Dog-On-Dog Aggression

Dog-on-dog aggression exists on a spectrum. Many dogs show warning signs long before a bite ever happens. Recognizing these early signals helps you intervene before things escalate.

Early Warning Signs

- Staring or freezing when another dog appears

- Stiff posture or raised hackles

- Lip licking, yawning, or turning away under tension

Escalation Behaviors

Dangerous Behaviors

- Repeated attempts to bite

- Biting with pressure or injury

- Inability to disengage even when separated

Offensive vs Defensive Aggression

Aggressive behavior does not always look the same. Some dogs move forward to intimidate or control a situation, while others react defensively because they feel trapped, overwhelmed, or afraid.

3 Reasons Why Dogs Become Aggressive Toward Other Dogs

Not all aggression is driven by the same motivations. Research shows that dog-directed aggression often follows patterns different from aggression toward people, and understanding this difference matters when evaluating risk and choosing the right training approach.

1. Assertiveness & Breed-Specific Tendencies

An extensive study on canine aggression found that many breeds show higher aggression toward unfamiliar dogs than toward unfamiliar people, and that this pattern is highly breed-specific. In other words, some dogs are far more likely to react aggressively to other dogs than to humans.

This pattern is more common in breeds historically developed for roles involving protection, herding, or animal control, where controlled assertiveness toward other animals was part of the job.

Importantly, this type of dog-directed aggression does not automatically predict aggression toward people.

- Breeds such as Akitas, Jack Russell Terriers, and Pit Bull–type dogs showed substantially greater aggression toward unfamiliar dogs than toward people.

- Other breeds — including Rough Collies, Miniature Poodles, and German Shepherds — have been found to have more generalized aggression toward people and other pets.

Want to learn more? Check out our article covering dog attacks by breed, including which dogs attack strangers, owners, and other dogs more often.

2. Fear, Anxiety & Environmental Stress

While genetics and historical function can influence behavior, many dogs show dog-on-dog aggression driven by anxiety, sensitivity, or defensiveness. In fact, one large-scale study found that highly fearful dogs have five times higher odds of aggressive behavior than non-fearful dogs.

When unfamiliar dogs feel unpredictable or threatening, fear-based aggression can serve to create distance. This type of aggression is often seen in dogs that:

- Missed early socialization opportunities

- Had negative experiences with other dogs

- Are anxious and sensitive to fast approaches or intense play styles

Fear-based aggression is often situational. It may worsen during life changes, high-stress periods, or when a dog feels overwhelmed by their environment.

3. Resource Guarding (Dogs, Space, Or People)

Some dogs become aggressive when they feel their space, food, toys, or human attention is being threatened. This can include guarding a handler on walks or reacting strongly when another dog approaches too closely.

These responses are rooted in insecurity and self-preservation, not dominance. Leashes can intensify guarding behavior by limiting a dog’s ability to move away from a perceived threat.

Watch: Resource guarding toward other dogs often overlaps with social tension and overstimulation. In this example, the dog growls when another dog approaches their owner. This behavior reflects boundary-setting rather than immediate intent to harm.

What About Frustration & Leash Reactivity?

Frustration is not a separate category so much as a common amplifier of dog-directed aggression.

Leashes restrict normal movement and communication between dogs. When a dog wants to approach, retreat, or disengage and cannot, frustration builds. Over time, that frustration can erupt as barking, lunging, or snapping.

This is one of the most common reasons dogs appear aggressive toward other dogs during walks, and it does not necessarily reflect fear or intent to harm.

What This Means for Owners

Dog-directed aggression:

- Does not automatically predict aggression toward people

- Is often shaped by breed history, socialization, and environment

- May be driven by fear, frustration, assertiveness, or a mix of factors

This is why responsible behavior management focuses on the individual dog, not just breed labels or assumptions.

What To Do If Your Dog Suddenly Becomes Aggressive

Seeing a sudden change in your dog’s behavior toward other dogs can be alarming. When a dog who was previously tolerant or social begins reacting aggressively, it’s a sign that something has shifted — and it deserves attention before you attempt training or behavior modification.

First Priority: Rule Out Medical Causes

Aggression that appears suddenly should always prompt a veterinary evaluation. Pain, illness, neurological changes, hormonal shifts, or sensory decline can all lower a dog’s tolerance and trigger defensive responses.

Red flags that warrant a vet visit include:

- Aggression that appears “out of nowhere”

- Reactions that escalate rapidly or feel out of character

- Aggression paired with limping, stiffness, or sensitivity to touch

- Changes in appetite, sleep, or energy

- Confusion, disorientation, or changes in vision or hearing

For a deeper breakdown of why dogs suddenly become aggressive, see our article covering sudden aggression in dogs.

Why Sudden Aggression Is Different From Lifelong Patterns

Dogs with lifelong dog-directed aggression typically show warning signs early and display consistent triggers over time. Sudden aggression, on the other hand, often reflects:

- Pain or physical discomfort

- Stress overload or emotional burnout

- A frightening or traumatic encounter

- Reduced ability to cope with normal social pressure

Because the cause is often situational or medical, treating sudden aggression as a training failure can make the problem worse.

How To Deal With Dog Aggression Toward Other Dogs (Action Plan)

Dog-on-dog aggression isn’t fixed with a single trick or quick correction. It improves through a combination of management, training, and gradual exposure, applied in the right order.

Think of this as a phased plan. Each phase builds on the one before it, and skipping ahead often makes things worse, not better.

Phase 1: Immediate Management (Safety First)

Management is not giving up. It’s how you prevent situations from escalating while you work on change.

Distance Is Your Best Tool

Aggression often flares when dogs are pushed past their comfort threshold. Creating distance reduces pressure and gives your dog room to stay regulated.

This may mean:

- Crossing the street

- Turning around early

- Using parked cars, fences, or hedges as visual barriers

Distance is one of the fastest ways to lower reactivity.

Avoid Forced Greetings

Face-to-face greetings, especially on leash, remove a dog’s ability to communicate and disengage naturally. For dogs with dog-directed aggression, forced interactions often trigger defensive or frustrated responses.

Your dog does not need to “say hi” to every dog they see.

Use Routes, Timing & Barriers Strategically

Choose quieter walking times and routes with space. Avoid bottlenecks, such as narrow sidewalks or trail entrances, where escape options are limited.

Management is about setting your dog up to succeed, not testing their limits.

Why Dog Parks Are Often a Bad Idea Here

Dog parks combine:

- High arousal

- Poorly matched play styles

- Unpredictable dogs

- Limited human control

For dogs struggling with dog-directed aggression, this environment often exacerbates problems rather than resolving them.

Phase 2: Training Foundations

Once safety is under control, training focuses on changing your dog’s emotional response rather than suppressing behavior.

Reward Calm Behavior

Calm doesn’t happen by accident. Reinforce moments when your dog:

- Notices another dog without reacting

- Looks back at you

- Chooses disengagement

You’re teaching your dog what to do, not just what not to do.

Work Below Threshold

Training is most effective when your dog can still think and learn. This means working at distances where they notice other dogs but remain responsive.

If your dog is already barking or lunging, learning has stopped. Increase distance and reset.

Build Focus & Disengagement

Skills like name response, eye contact, and voluntary check-ins become powerful tools when dealing with triggers. These aren’t obedience tricks. They’re coping strategies.

Progress here is often subtle. That’s normal.

Phase 3: Controlled Exposure (When Appropriate)

Exposure helps only when it’s done carefully and at the dog’s pace.

Why Flooding Makes Things Worse

Flooding forces a dog into close contact with triggers until they stop reacting. This may look like progress, but it often increases fear and suppresses warning signals.

Suppressed behavior is not the same as changed emotion.

When Socialization Helps — And When It Doesn’t

Socialization can help when:

- The dogs are well-matched

- It’s gradual

- Distance and exits are available

It does not help when dogs are overwhelmed, restrained, or forced to “tough it out.” Check out our guide on how to properly introduce dogs for additional tips.

What NOT To Do If Your Dog Is Aggressive Toward Other Dogs

Some common advice does more harm than good.

- Do not punish growling. Punishing it teaches dogs to skip warnings and escalate directly to biting.

- Avoid dominance-based methods. Techniques based on “showing who’s boss” increase fear, suppress signals, and damage trust.

- Do not rely on dog parks to fix aggression. Unstructured, high-arousal environments are not training tools.

- Never “let them work it out.” Dog fights can escalate quickly and cause lasting physical and behavioral damage.

Tools That Can Help (And Tools That Can Make Things Worse)

The right tools won’t “fix” dog-on-dog aggression on their own, but they can make management and training safer, more effective, and less stressful for everyone involved.

The wrong tools, on the other hand, often suppress warning signs, increase fear, and make aggressive behavior more dangerous over time.

4 Tools That Can Assist

Tools that help with dog-on-dog aggression don’t aim to control or suppress behavior. They aim to increase safety, reduce stress, and give your dog clearer options for disengaging.

1. Harness vs Collar

For many dogs struggling with dog-directed aggression, a front-clip or back-clip harness provides better control without adding neck pain or pressure.

Harnesses:

- Reduce strain on the neck and spine

- Give handlers more control during sudden reactions

- Lower the risk of escalating fear-based responses

Collars can still be appropriate in some situations, but dogs prone to lunging or freezing often benefit from the added stability of a harness.

2. Long Lines (Used Correctly)

Long lines allow dogs to move more naturally while still maintaining safety and control. When used in open spaces, they can:

- Reduce frustration caused by tight leash restriction

- Support training at a comfortable distance

- Allow gradual exposure without forced proximity

Long lines should not be used in crowded areas or wrapped around the handler’s body, but they can be valuable tools when space allows.

3. High-Value Treats

Food is one of the most powerful tools for changing emotional responses. High-value treats help dogs:

- Stay engaged with their handler

- Associate the presence of other dogs with positive outcomes

- Recover more quickly from stressful moments

For many dogs, standard kibble isn’t motivating enough in challenging environments. Soft, smelly, easy-to-eat treats often work best.

4. Muzzle Training (When Appropriate)

Muzzles are often misunderstood, but when introduced properly, they can be neutral safety tools rather than punishments.

A well-fitted, basket-style muzzle:

- Allows panting, drinking, and treat delivery

- Adds a layer of safety during training

- Can reduce handler anxiety, which dogs often pick up on

Muzzle training should always be gradual and positive. A muzzle is not a solution by itself, but it can make training safer for everyone involved.

Tools & Methods That Can Make Things Worse

Some tools and techniques may appear to stop aggression in the moment but actually increase risk over time.

Punishment-Based Tools

Tools designed to correct or suppress behavior through discomfort often silence warning signs without addressing the underlying emotion.

This can lead to:

- Increased fear or anxiety

- Suppressed growling followed by sudden biting

- Escalation rather than resolution

Shock, Choke & Dominance-Based Methods

Methods that rely on pain, intimidation, or “showing who’s boss” are not supported by modern behavior science.

These approaches:

- Increase stress and reactivity

- Damage trust between dog and handler

- Do not teach dogs how to cope with triggers

Aggression driven by fear, frustration, or overstimulation cannot be safely corrected through force.

A Note On Tools & Progress

No tool replaces thoughtful management and training. The goal is not control at any cost, but helping your dog feel safe enough to make better choices.

If a tool increases fear, tension, or shutdown, it’s working against you — even if it appears effective in the short term.

Progress Expectations: What Improvement Really Looks Like

When you’re working on dog-on-dog aggression, progress rarely looks dramatic. There are no overnight transformations and no moment where your dog suddenly loves every other dog they see.

Real improvement is quieter, slower, and often easier to miss if you don’t know what to look for.

Distance, Duration & Recovery

Behavior change shows up in three key ways:

- Distance: Your dog can tolerate other dogs from farther away without reacting.

- Duration: Your dog can notice another dog for longer before stress builds.

- Recovery: When a reaction does happen, your dog calms down faster and returns to baseline more easily.

Even small gains in any one of these areas are meaningful. A few extra feet of comfort or a faster recovery time is progress, not failure.

Why “Calm Coexistence” Is Often Success

For many dogs, the goal is not social play or friendly greetings. The goal is calm coexistence.

That means:

- Walking past other dogs without incident

- Sharing space without tension

- Ignoring, disengaging, or choosing neutrality

A dog who can remain calm and functional around other dogs is succeeding, even if they never become social butterflies.

Why Setbacks Are Normal

Progress is not linear. Stressful days, surprise encounters, illness, or environmental changes can all cause temporary regressions.

A setback does not erase progress. It usually means:

- Your dog was pushed past their current threshold

- Management needs adjusting

- Recovery time was needed

What matters is the overall trend over time, not a single bad walk.

A More Helpful Way To Measure Progress

Instead of asking: “Why isn’t this fixed yet?”

Try asking:

- Is my dog reacting less intensely than before?

- Are we avoiding fewer situations because we have better tools?

- Is my dog recovering more quickly after stress?

Those answers tell a much more accurate story.

Quick Start Checklist: If Your Dog Is Aggressive Toward Other Dogs

If walks feel stressful or unpredictable, start here. This checklist focuses on immediate safety, clarity, and forward momentum, not quick fixes.

- Prioritize distance immediately. Distance lowers emotional intensity fast.

- Stop forced greetings. These interactions remove choice and often escalate tension, even in dogs that are otherwise social.

- Observe triggers, not just reactions. Distance, speed of approach, size of the other dog, leash tension, location, and time of day all matter.

- Rule out medical causes. If aggression appeared suddenly or escalated quickly, schedule a vet check.

- Switch to management mode. Use routes, timing, barriers, and tools that reduce exposure while you work on training.

- Reward calm, not just obedience. Mark and reward moments when your dog notices another dog without reacting.

- Avoid punishment. Suppression increases risk by removing warning signals without changing the emotion behind them.

- Adjust expectations. Calm coexistence, quicker recovery, and increased tolerance are real wins.

- Get professional help when needed. If aggression feels unpredictable, intense, or unsafe, work with a qualified force-free trainer or veterinary behaviorist.

You don’t need to fix everything at once. Start by keeping everyone safe and reducing stress. Training works best when emotions are manageable.

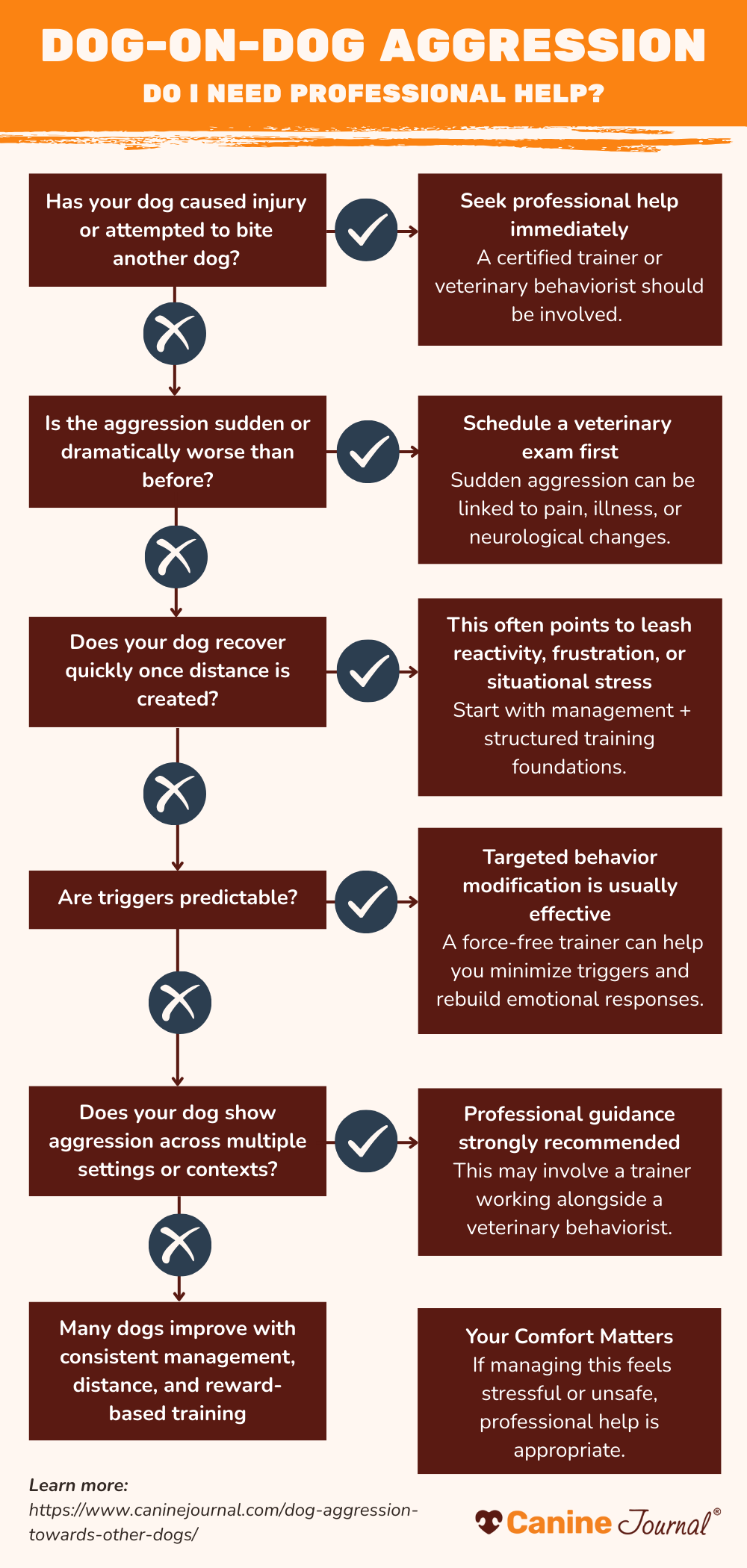

When Professional Help Is Necessary

Many dogs with dog-on-dog aggression improve with thoughtful management and training. But there are situations where working alone isn’t enough, and bringing in professional help is the safest and most effective next step.

Seeking help is not a failure. It’s often the smartest move you can make.

When Training Alone Isn’t Enough

You should strongly consider professional support if:

- Aggression is escalating in intensity or frequency

- Your dog has attempted to bite or caused injury

- Reactions happen with little warning or recovery

- You feel anxious, overwhelmed, or unsure how to keep others safe

- Progress has stalled despite consistent, force-free training

- Aggression appeared suddenly or changed dramatically

In these cases, continuing without guidance can increase risk for your dog, other dogs, and you.

Trainer vs. Behaviorist: What’s the Difference?

Not all professionals serve the same role. Understanding the distinction matters.

Certified Dog Trainers

- Focus on behavior modification and skill-building

- Work on desensitization, counterconditioning, and management plans

- Best for mild to moderate dog-directed aggression

Look for trainers who use force-free, evidence-based methods

Veterinary Behaviorists

- Are licensed veterinarians with advanced training in animal behavior

- Can diagnose medical contributors and prescribe medication if needed

- Best for severe, unpredictable, or dangerous aggression

- Often work alongside trainers for a comprehensive plan

If aggression is intense, sudden, or accompanied by anxiety, medication may be part of a humane and effective treatment plan.

What Credentials Actually Matter

Avoid trainers who rely on dominance-based language or punishment tools. Instead, look for professionals who hold recognized certifications, such as:

- CPDT-KA or CPDT-KSA

- IAABC certification

- KPA (Karen Pryor Academy)

- DACVB (for veterinary behaviorists)

Experience with dog-directed aggression specifically matters more than generalized obedience credentials.

What Professional Help Should Look Like

A qualified professional should:

- Prioritize safety and management first

- Explain why behaviors are happening, not just how to stop them

- Customize plans based on your dog’s triggers and thresholds

- Avoid guarantees or “quick fixes”

- Emphasize gradual, measurable progress

If a trainer dismisses fear, encourages confrontation, or promises instant results, keep looking.

When Rehoming Enters The Conversation

In some cases, rehoming may be discussed as part of a responsible, welfare-focused plan. This is not a punishment and not a decision made lightly.

Rehoming is typically considered when:

- Aggression poses ongoing safety risks

- Resources for management or training are limited

- The dog’s needs exceed what the current environment can safely provide

This conversation should always be guided by professionals and framed around quality of life, not blame.

Breed, Size & Reality Checks

Breed and size often come up in conversations about dog-on-dog aggression, but they’re also some of the most misunderstood factors. Risk is not about labeling certain dogs as “bad.” It’s about understanding context, management, and historical purpose.

Breed data can be useful when it’s treated as background information, not a prediction tool.

What Breed Data Can — And Can’t — Tell Us

Across multiple studies and large-scale datasets, certain breeds appear more frequently when researchers examine dog-directed aggression specifically. That does not mean these dogs are more dangerous overall, nor does it mean individual dogs will behave the same way.

Breed data reflects:

- Historical roles and selective breeding

- Typical responses to social pressure from other dogs

- How dogs may behave without adequate management or training

It does not determine:

- A dog’s personality

- Their behavior toward people

- Their ability to improve with training and management

For broader context on how breed data is often misinterpreted, see our articles on dog attacks by breed and dog bite statistics.

Breeds Linked To Dog-Directed Aggression

When researchers focus specifically on aggression toward other dogs, the following breeds tend to reappear across studies:

- Akita

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Boxer

- Chihuahua

- Cocker Spaniel

- Dachshund

- English Springer Spaniel

- German Shepherd

- Jack Russell Terrier

- Pit Bull–type dogs

- Rottweiler

- West Highland White Terrier

Importantly, these trends are distinct from human-directed aggression. For a broader discussion of how aggression is categorized across breeds, see our article covering aggressive dog breeds, keeping in mind that lists describe patterns, not outcomes.

What Actually Matters More Than Breed

Across studies and real-world cases, the strongest predictors of dog-on-dog aggression are not breed alone, but a combination of individual traits, life stage, and handling.

- Age: Older dogs have higher tendency towards aggressive behavior than younger dogs, often due to reduced tolerance, pain, or discomfort.

- Sex: ale dogs are statistically more likely to display aggressive behavior toward other dogs than females, particularly in same-sex interactions.

- Size: Smaller dogs may display aggressive behaviors more frequently than medium or large dogs, especially warning behaviors like barking or snapping.

- Fearfulness: Fear is one of the strongest predictors of aggression across all breeds and sizes.

- Owner experience: Environment and handling play a major role in whether aggression escalates or improves.

Can Dog-On-Dog Aggression Be Prevented?

Not every case of dog-on-dog aggression can be prevented, but many cases can be reduced or avoided with the right foundations. Prevention isn’t about forcing friendliness. It’s about teaching dogs how to feel safe, regulated, and supported around other dogs.

Early Exposure, Done Right

Early exposure matters, but how it’s done matters more than how much. Healthy exposure:

- Is gradual and age-appropriate

- Prioritizes neutral or positive experiences

- Avoids overwhelming environments

- Allows puppies to disengage freely

Poorly managed exposure, forced greetings, or chaotic dog parks can actually increase the risk of future aggression. Socialization should build confidence, not tolerance through stress.

Learning To Read Dog Body Language

Most dogs communicate discomfort long before they react aggressively. Learning to spot early signals allows you to intervene before things escalate.

Watch for:

- Freezing or stiff posture

- Hard staring or sudden stillness

- Lip licking, yawning, or turning away under tension

- Raised hackles or a closed, tight mouth

Responding early by creating distance protects your dog and reinforces trust.

Advocate For Your Dog

One of the most effective prevention tools is advocacy. This means:

- Saying no to unwanted greetings

- Creating space when your dog needs it

- Leaving situations that feel off

- Choosing environments that match your dog’s comfort level

Advocating for your dog reduces pressure and teaches them they don’t need to handle uncomfortable situations alone. Prevention isn’t about controlling your dog. It’s about removing the need for aggressive responses in the first place.

Frequently Asked Questions

Dog-on-dog aggression raises a lot of questions, especially when advice online is conflicting or overly simplistic. These answers address the most common concerns owners have, with realistic expectations and science-backed guidance.

Can Dog-On-Dog Aggression Be Cured?

There’s no single “cure,” but many dogs improve significantly with the right combination of management, training, and support. The goal is safer behavior and lower stress, not forcing friendliness.

Will My Dog Ever Be Able To Meet Other Dogs?

Some dogs can learn to socialize safely. Others do best with calm coexistence and limited interaction. Success looks different for every dog.

Is Growling Always A Bad Sign?

No. Growling is communication. It’s often a warning signal that helps prevent escalation. Punishing growling increases risk by removing that warning.

Are Some Breeds More Aggressive Toward Other Dogs?

Some breeds appear more often in dog-directed aggression research, but breed alone does not predict individual behavior. Context, fear, handling, and environment matter more.

Should I Avoid Other Dogs Completely?

Avoidance can be a helpful short-term management strategy, but long-term plans usually focus on reducing stress and improving coping skills rather than permanent isolation.

When Should I Seek Professional Help?

If aggression feels unsafe, unpredictable, or overwhelming — or if progress has stalled — working with a qualified professional can make a major difference.

Dealing With Hostility & Other Behavior Issues

Dealing with dog-on-dog aggression can be overwhelming, but you can help your dog relax when other dogs are around with a little guidance. However, this probably won’t be the only behavioral issue you come across as a dog owner.

No matter what behaviors you and your dog are dealing with, our expert team is here to help. We have articles on barking, separation anxiety, whining, and more to help you find ways to correct undesirable behaviors and keep your pup happy and safe.